Bacon-Wrapped Existentialism - Jean-Paul Sartre and Francis Bacon

It was a rainy evening when Francis strolled into a small bar in Paris. He visibly monitors the room to see folks sitting four and five in the round at small tables meant for two. The waitstaff makes themselves thin while tip-toeing through the small gaps between the patron’s chairs. Light ochre-stained walls create a small perimeter of a smoke-filled chamber impregnated with the chatter of philosophy, art, literature, drugs, religion, and war. In the corner of the room adjacent to the bar sits a small glassy-eyed fellow with round spectacles and a less than perfect complexion, with his head down, scribbling profusely in a small notebook. Francis weaves his way through the chatter to find an empty chair across from the small-statured man, a cigarette burns in a square glass ashtray on the table between them. “Hello Francis," says the kindness eye-filled man, “what can I help you with this evening?” As he sets his pen down on top of the word-crammed pages of the notebook, looking at a partially smoke filtered dark-headed man before him. Francis cocks a half-smile and responds, “I long for people to tell me what to do, to tell me where I go wrong (Sylvester, 77).” The small man with bloodshot eyes looks at Francis over the rim of his round glasses, takes a drag off his square, and says, “Francis, no one can tell you what to do. You are completely free to decide for yourself what it is you should be doing. You are condemned to be free: because once cast into the world, you are responsible for everything that you do (Sartre, 29).”

This conversation never occurred of course, from what my research can tell me, the painter Francis Bacon and Philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre never actually met, much less carried on a dialogue of this nature. Just the same, they are both champions of the movement so deemed, Existentialism. At this point in time for philosophy and art, God was dead. Friedrich Nietzsche had stumbled across the corpse, but it was Kant whose fingerprints were all over the murder weapon (Landau, 142). Mankind was trying to find a path in which to explain the meaning of life. Existentialism stepped in and became the philosophy of choice for a post-war era in Europe. Religion and morality had been smashed in the teeth and man was not left alone with his vices. Sartre had derived a saying of “existence precedes essence, what he meant by this was a man first exists: he materializes in the world, encounters himself, and only afterward defines himself. If man, as existentialists conceive of him, cannot be defined, it is because, to begin with, he is nothing. He will not be anything until later, and then he will be what he makes of himself (Sartre, 22).” While Sartre was philosophizing about life, angst, alienation, disgust, anxiety, and freedom for his fellow man, Francis Bacon was painting with the angst and freedom that Sartre was theorizing about.

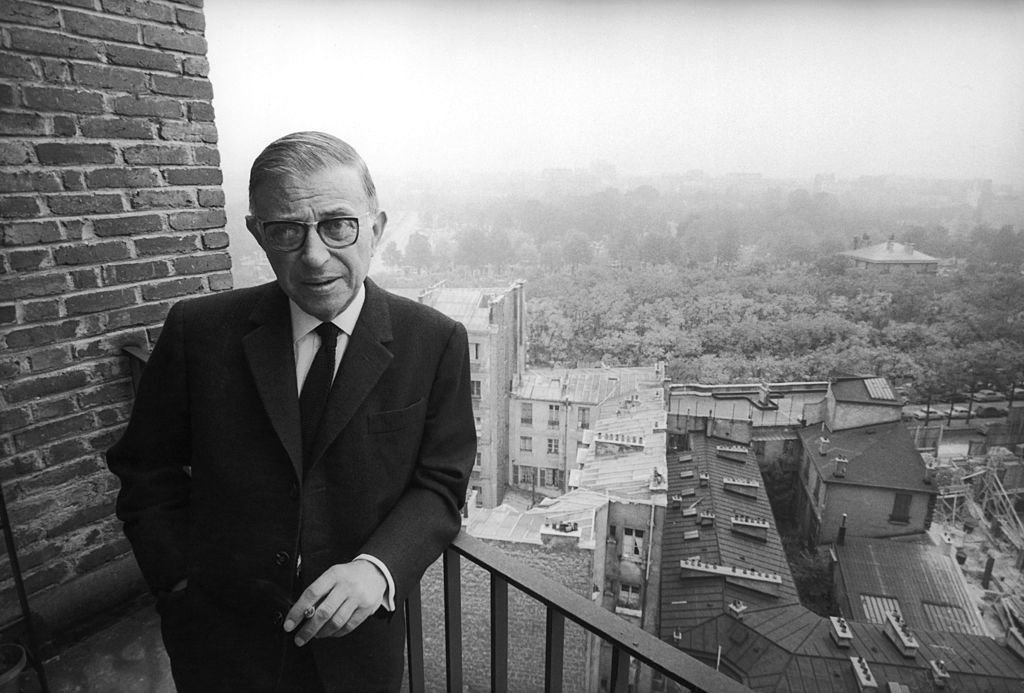

Jean-Paul Sartre was a man full of philosophical words who began by studying Husserlian phenomenology and “it was this groundwork that freed Sartre and other existentialists to write so adventurously about everything from cafe waiters to trees to breasts. Reading his Husserl books in Berlin in 1933, Sartre developed his own bold interpretation of it, putting special emphasis on intentionality and the way it throws the mind out into the world and its things. For Sartre, this gives the mind immense freedom (Bakewell, 46).” Jean-Paul would also study the work of philosopher Soren Kierkegaard and his rebellious nature. It wasn’t long before Sartre was discussed Kierkegaard’s ideas of dealing with angst by turning to God. Sartre’s lack of theology left him turning his back on Kierkegaard and his beating heart for the Messiah. Sartre would soon find some common ground in the ideas of Nietzsche along with his Godless existentialist crowd. Although Jean-Paul was an atheist wonder, it was his romantic idea of man that made him a beloved philosopher. He said, “As far as men go, it is not what they are that interests me, but what they can become (Landau, 175).” Jean-Paul lived his philosophy of freedom which is why he had a lifelong open relationship with his lover and fellow writer Simone de Beauvoir. Although his sex life was less than moral from a Christian standpoint, he nevertheless inspired his fellow man with his ideas of men bettering themselves for both the individual and society at large. Even Martin Luther King, Jr., read Sartre while working on the Civil Rights movement. Upon Jean-Paul’s death in 1980 some fifty-thousand people attended his funeral proceedings. Obviously, he touched many of his fellow Homo sapiens. “Through the choices, I make in my life I point a picture of what I think a human being ought to be like. If I do this sincerely it is a great responsibility (Warburton, 199).”

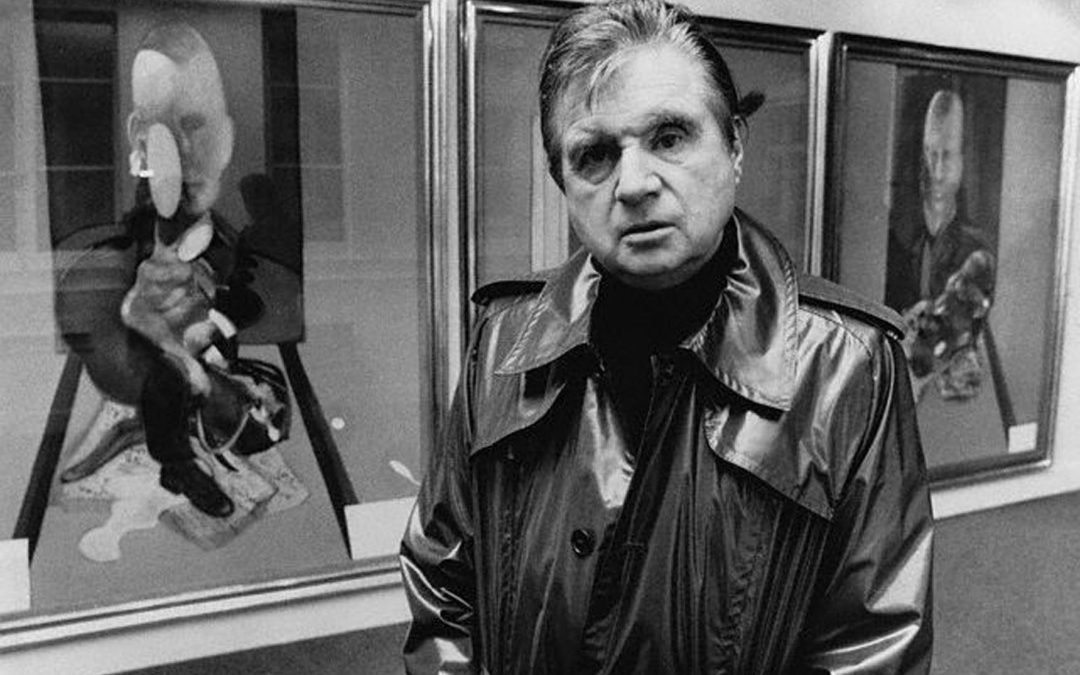

Francis Bacon was an interesting fellow, to say the least. Born in Dublin Ireland to British parents, whom he was basically estranged from, never having a healthy relationship with either of them. His mother referred to him as a drifter and neither parent was happy about his becoming a painter. Bacon’s father kicked him out of the house when he was sixteen after finding Francis trying on his grandmother’s unmentionables (Ficacci, 91). From a young age, he was becoming aware of his homosexuality. In an interview with David Sylvester, he recalls his feelings about his father, saying, “I disliked him, but I was sexually attracted to him when I was young. When I first sensed it, I hardly knew that it was sexual. It was only later, through the grooms and the people in the stables I had affairs with, that I realized that it was a sexual thing towards my father (Sylvester, 82).” Bacon’s father was a trainer of racehorses and it was at the stables his father worked where he met the lovers that he spoke of.

Francis was an avid fan of Michelangelo and Van Gogh but was not enthralled with Picasso or Matisse. He called Matisse, “Too lyrical and decorative (Sylvester 204).” The irony is quite stunning when talking about his discord for Picasso, given that he mentions taking up painting after seeing an exhibition of Picasso, “At that moment I thought, well I will try and paint too (Sylvester, 210).” He also despised abstract expressionism, saying, “Painting is a duality, and abstract painting is an entirely aesthetic thing. It always remains on one level. It is only interested in the beauty of its patterns or its shapes.” He goes on to accuse abstraction of being too weak to convey emotion. “There’s never any tension in it.” (Sylvester, 67-68) In a later interview with Sylvester, Francis refers to abstract expressionism as being sloppy. I can’t say that I share the same feelings with Bacon when it comes to the abstract expressionists, maybe his disgust was competitive since they were American counterparts of the existentialists, but I do share his loathing of Matisse’s decorative nature.

Like most of the Existentialists, Francis was not a church-going man although he did paint many canvases of the Pope and his variations on the crucifixion of Christ. One would almost refer to this as a mockery of the Christian faith, and I’m certain they would most likely scream blasphemy, but that wasn’t Bacon’s intent. Francis referred to himself as an observer and he found he was enamored with the Velasquez portrait, Pope Innocent X. He painted several versions of the pope with a common vision of the scream that we see depicted in many of his works, including that of Paining 1946.

Painting 1946 by Francis Bacon

When describing Painting 1946, Luigi Ficacci wrote, “The level of expressive violence in the painting executed immediately before and after World War II, was immediately rocked in Painting 1946 by an agonizing inspiration that was so extreme as to force harsh, pointed and previously unknown characters into the picture. The most powerful of these is a ferocious sarcasm that reveals a recurrent expressive motif in Bacon’s work: violent humor that is often disproportionate, grotesque, cynical, and outrageous. The snarling mouth of the monster that is the protagonist of Painting 1946, produces an indefinable impression, between a sardonic smile and the asthmatic effect of an imposter emerging from the plethoric, dark oppression. Within the overall sense of macabre repulsion and horror from the perverse, blind violence inherent in the figure, here again, no explicit content and no literal significance can be deciphered in the painting. Through its monumental display of incongruous juxtapositions, Painting 1946 imposes the condition of absurdity as a coherent expressive reality (Ficacci, 21-23).” While this is exquisitely written it is just as preposterously unjustified. Absurdity wrapped in babble and dunked ludicrously into balderdash left dripping with poppycock for us to be mesmerized by. Francis himself would be nauseated by these attempts to draw Freudian-like conclusions from his work. Bacon himself has discussed the matter of people over-analyzing his imagery. Here’s the skinny on Bacon, he was not a formally trained artist. He never once studied art outside of visiting museums to view paintings that he enjoyed, among which were those of Rembrandt. When discussing his fascination with meat Francis said, “I have never tried to be horrific. One only has to have observed things and know the undercurrents to realize that anything that I have been able to do hasn’t stressed that side of life. When you go into a butcher’s shop and see how beautiful meat can be and then you think about it, you can think of the whole horror of life-of one thing living off another. (Sylvester, 53-54).” He just appreciated the meat and the colors associated with it. This does seem a little strange to a casual observer and that’s probably the reason so many critics tried to put an underlying meaning to it. Again with the scream that reoccurs in many of Bacon’s paintings, people want to slap a label on the intent, but Francis was just enamored with the mouth and its shape. He mentions a book that he once bought with hand-colored depictions of diseases of the mouth, which he became obsessed with for a time but later lost that obsession. I will admit and Bacon may have as well, there are probably some underlying traumas in his life that come across unconsciously in his work. For the most part, though, he painted things that he enjoyed or found fascinating. Painting 1946 actually started as a chimpanzee in a grassy field before morphing into a bird of prey and then ultimately being destroyed again by Francis to resurrect itself into the finished product that it became. There’s really no way to describe it truthfully. We may think it’s grotesque but Bacon saw it as beautiful in his own free way.

Francis Bacon certainly lived a Sartrean life, he existed, worked on his essence, and did so within his own chosen freedom. He was never a slave to anyone’s ideas or restrictions of what he was expected to be. Not by his parents, not but the art world at large, or even by life. “I think of life as meaningless, but we give it meaning during our own existence. We create certain attitudes which give it a meaning while we exist, though they in themselves are meaningless, really (Sylvester, 153).” That my friends is what I like to refer to as, “Bacon Wrapped Existentialism!”

Works Cited

Bakewell, Sarah. At the Existentialist café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails. Chatto & Windus, 2016. p. 46

Ficacci, Luigi, and Bradley Baker Dick. Francis Bacon, 1909-1992: Deep beneath the Surfaces of Things.Taschen, 2017. p. 21-23, 91

Landau, Cecile, et al. The Little Book of Philosophy. DK Publishing, 2018. p. 142, 175

Sartre, Jean-Paul, et al. Existentialism Is a Humanism: (LExistentialisme Est Un Humanisme).

Yale University Press, 2007. p. 22, 29

Sylvester, David, and Francis Bacon. Interviews with Francis Bacon: The Brutality of Fact. Thames & Hudson, 2016. p. 53, 54, 67, 68, 77, 82, 153, 204, 210

Warburton, Nigel. A Little History of Philosophy. Yale University Press, 2012. p. 199

Artwork

Bacon, Francis. Painting 1946. 1946, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Link to Painting 1946: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79204